Fork proofs

A fork is a split in the blockchain, and it is created by malicious validators who produce two or more micro blocks at the same block height and view number. Only malicious validators will create or build on a fork, mostly to attempt a double-spend attack. Forks can only happen in micro blocks since macro blocks are forkless and produced with Tendermint.

There are two ways to end a fork:

- When a rational validator is selected to produce the next micro block. A rational validator will not build on a fork, since it would get the view slot punished.

- When the next block is a macro block since macro blocks have finality, therefore, are forkless.

Mind that, even though the validator is who misbehaves, it is the view slot that gets punished. Hence, a validator can have multiple view slots in the validator slot list, but only the view slot that forked the chain gets punished.

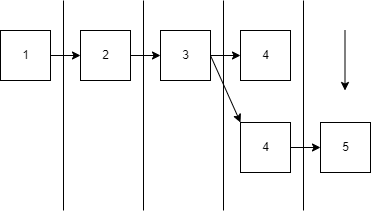

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows a fork of length one at block height 4. The view slot randomly selected to produce block 4 is a malicious validator. This validator produces two blocks with the same block number and view number. Next, assuming that the producer of block 5 is a rational validator, this validator chooses which chain to continue to produce on and, by doing so, end the fork.

Note that when a rational validator ends a fork, it can submit a fork proof in the micro block. However, fork proofs are optional, so it seems reasonable to a rational validator to submit fork proofs, but these validators can end the fork simply by choosing a single chain to build on.

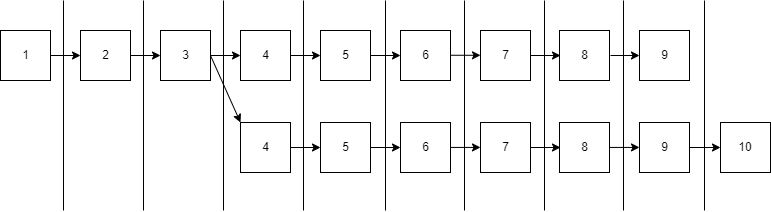

Figure 2

Using figure 2 as a reference, we can see that several validators continued to build on the fork, and a rational validator ended the fork in block 8. Supposing a rational validator was not selected to produce the next micro block, the fork would have ended at the next macro block.

Fork proof

To prove that a malicious validator forked the blockchain, a rational validator must include a fork proof in a micro block. Note that any fork in figure 2 can be a reference to a fork proof. Therefore, the fork proof applies to those who have started the fork but also to those who have continued.

A fork proof can be submitted from the micro block immediately after the fork occurred until the macro block at the end of the next batch. That ensures enough time for a rational validator to include fork proofs before the rewards are distributed. This is necessary as the rewards of the misbehaving view slots are burned.

View slots sign the blocks they have produced, so these signatures can prove that a view slot has misbehaved. The fork proof consists of the header of each micro block and the respective micro block justification, exemplified in figure 1, block 4:

Header 1 MicroHeader: the micro block header of block 1

Header 2 MicroHeader: the micro block header of block 2

Justification 1 SchnorrSignature: Compressed signature of the block producer of block 1

Justification 2 SchnorrSignature: Compressed signature of the block producer of block 2

Previous VRF seed VrfSeed: the random seed from the previous block.

Observe that both blocks are from the same view slot.

Probability in continuing a fork

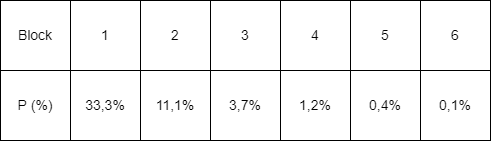

According to the Albatross security assumption, given that the validator slot list is 3𝑓+1, we have at most f malicious validators.

The probability of d view slots being owned by malicious validators decreases one-third in every block produced after forking the chain, following the next equation.

The probability decreases rapidly, as shown in the following table:

Figure 3